by Justin Muhl and Josh Klemm

As delegates converge at COP26 in Glasgow this week, many are promoting the notion of hydropower as central to weaning our energy systems off of fossil fuels. Yet hydropower generates significant greenhouse gases, particularly methane, and is one of the most vulnerable energy technologies to the impacts of climate change.

Climate change is driving increasingly severe weather events, from devastating floods in Europe and China, to prolonged drought in the western U.S. and Brazil. Hydropower relies on river flows and so is particularly exposed to these effects, which are only expected to become more serious over time. In recent years, we have seen countries from Brazil to Zambia grapple with the effects of years-long droughts on hydro-dependent energy systems. The economic impacts of losing power at just the time it is most needed have already been significant.

The increasing unpredictability of hydropower as a result of climate change poses real challenges to energy planners tasked with managing electricity grids, and real risks for financiers in the energy sector. This is discussed in a new briefing paper on the impacts of climate change for the financial viability of new hydropower projects.

The paper draws on some of the latest scientific research, recent accounts of climate-related impacts on hydropower, as well as analysis of five in-depth cases using the Riverscope assessment tool. Developed by TMP Systems, Riverscope is the first comprehensive tool to assess often-overlooked environmental and social risks and connect them quantitatively to the commercial performance of hydropower projects. It uses geospatial analysis and a robust quantitative methodology to evaluate commercial risk in the hydropower sector.

Using Riverscope assessments as a baseline, the briefing paper finds that even relatively modest climate impacts on hydropower generation would have a detrimental impact on project finances. In the case of the proposed Koukoutamba dam in Guinea, for example, an average 5% annual reduction in output would lead to a Net Present Value (NPV) loss of $110 million. The same climate scenario amounted to an average loss of $189 million across the cases examined. This would make power from these projects prohibitively expensive and risky for financiers, and would further dampen their cost competitiveness against readily available solar options.

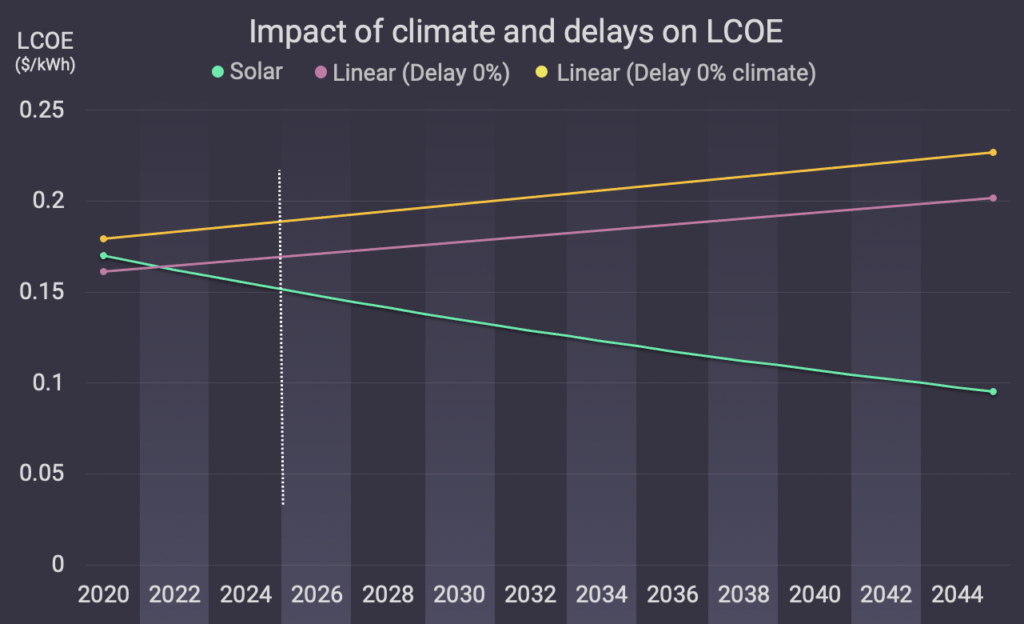

As the graph below indicates, these climate impacts would lead to an 11% increase in the Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) from original projections. This means that even if Koukoutamba were online today, local solar options would already be cheaper per kilowatt hour. But by 2025, the earliest possible point of operation, this added climate exposure would make Koukoutamba 25% more expensive than local solar alternatives. Such financial impacts of climate change on large hydropower projects are likely to grow over time as climate impacts worsen.

Some key takeaways from the climate assessment include:

- Hydropower is a contributor toward climate change. Tropical reservoirs are known for their considerable GHG emissions which directly contribute to global warming, while hydropower indirectly contributes to climate change through deforestation.

- Increasingly unpredictable climate impacts could directly affect the output of hydropower plants during periods of drought, while climate-induced flooding can add to construction delays and cost overruns, as well as threaten dam safety.

- Energy planning needs to be more systematic in its approach to account for the climate and cumulative impact of dams, amongst other environmental, social and commercial factors.

- Much more extensive efforts are needed to exhaust alternative options before dams are developed, and much better monitoring and regulatory systems are needed to avoid the worst climate impacts of hydropower.

As the briefing paper demonstrates, large hydropower is not necessarily an effective weapon in the climate fight, but is rather a growing chink in the armor. As the climate crisis continues to take hold, and given that hydropower is directly reliant on water regimes, large dams will only become more vulnerable to climate extremes. Both the financial and climate justifications for promoting hydropower do not hold water, and as negotiations get underway in Glasgow, policymakers should take note.

Justin Muhl is an Associate at TMP Systems. Josh Klemm is the Policy Director at International Rivers.

Featured photo: Dried up Mekong River in Thailand by Khong Jiam