By Pai Deetes, Regional Campaigns and Communications Director, Southeast Asia Program

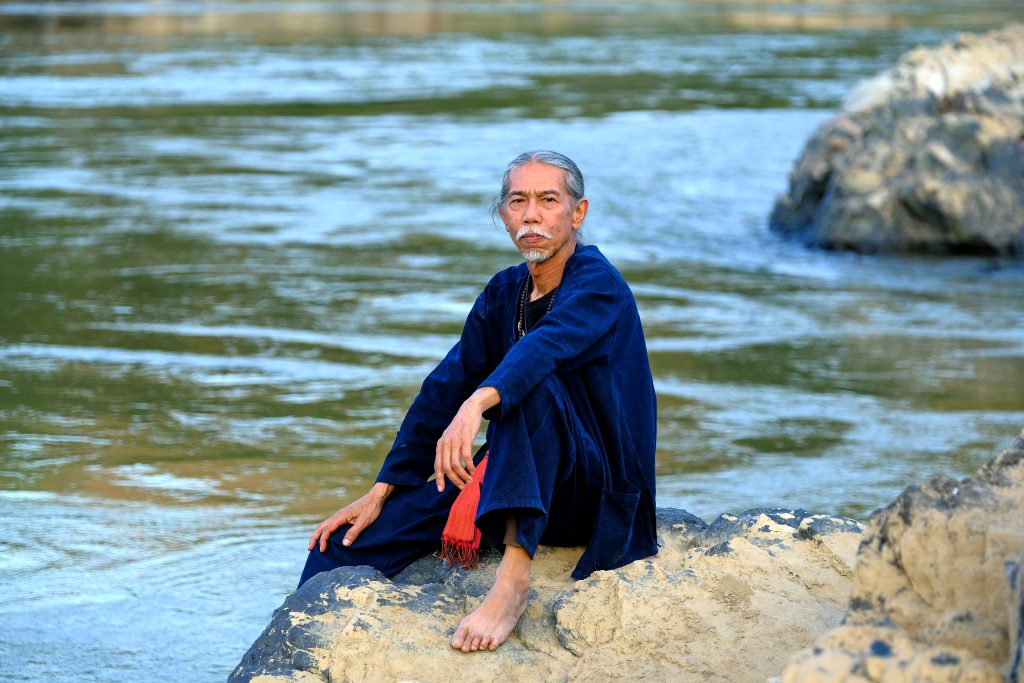

Today, Niwat Roykaew of Chiang Khong Conservation Group is a recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize, for a momentous win for the Mekong River where the Thai Cabinet formally called for the cancellation of the Lancang-Mekong Navigation Channel Improvement Project, known as the Mekong “rapids-blasting” project. The cabinet decision was the culmination of decades of campaigning by Thai Mekong communities and civil society groups, aided by environmentalists, who have worked tirelessly to raise concerns over the China-led project and the future it would represent for the Mekong.

Watch the story of Goldman Prize winner Niwat Roykeaw of Chiang Kong Conservation Group who won for protecting the Mekong river from the Mekong Rapid blasting for navigation from Yunnan to Luang Prabang.

BACKGROUND

The Mekong rapids-blasting project had been on government agendas for almost twenty years. In 2000, China, Myanmar, Laos and Thailand signed the Agreement on Commercial Navigation on the Lancang-Mekong River, initiating studies to examine the feasibility and impacts of the project. The project aimed to remove rapids from stretches of the Mekong River through dredging and blasting, enabling year-round navigation of 500-tonne freighters between southern China’s Yunnan Province to the Thai-Lao border and on to Luang Prabang in Laos. Under this plan, the Mekong would be converted into a channelized waterway for commercial navigation. The project has since been implemented in stretches of the Mekong in China, Myanmar and along the Lao border, up to the Thai border at the Golden Triangle.

But for Niwat, and Thai communities living along the Mekong and local organizations such as the Chiang Khong Conservation Group, the project raises grave concerns over threats to the river ecosystem, critical fish habitat and breeding grounds, and local livelihoods and culture.

A DECADE OF RESISTANCE

For over ten years, the proposed channelization in Thailand was suspended by previous Thai governments, citing concerns over environmental impacts and issues of sovereignty and national security at the Thai-Lao border. However, in late 2016, the project developer, China CCCC Second Harbor, initiated consultation meetings in Thailand, indicating the project had been revived. In a decision that shocked communities and environmental groups, the Thai Cabinet adopted a resolution supporting China CCCC Second Harbor’s plans for exploration and development of the project.

Following sustained local campaigning, the project took a number of twists and turns. In late 2017, Thailand’s Foreign Minister Don Pramudwina announced that China had decided to step back from its plan for rapids blasting, acknowledging that the project would hurt communities living along the river. However, during 2017-2018, consultation meetings and preparatory work on the project continued, prolonging uncertainty for local communities fighting to conserve the character and rich resources of the Mekong.

During the past three years, the Chiang Khong Conservation Group and the Thai Mekong People’s Network have dedicated their efforts to convey their concerns to multiple actors, including Thai Parliamentary committees and national security bodies. The community campaign also received important support from academics and journalists.

I recall a pivotal campaign moment in April 2017, which gave a glimpse into what was possible. Only a few months into the ‘survey and design’, then underway by the Chinese company amid extensive protest and community actions, Niwat was invited by the provincial military commander to a meeting. I accompanied him. The commander opened the meeting by informing Niwat that it was the government’s project so no one should oppose it. But within an hour, Niwat had successfully convinced everyone in the Army meeting room.

“When we started the campaign in the early days, locals asked me how ordinary people like us could fight to protect the Mekong, as it was a regional issue involving powerful state and non-state actors,” Niwat said. “But this proves that we can do it, with evidence-based campaigns. At last, this project is officially canceled. But major problems still exist for the Mekong River, with more dams in the upper reaches, and in the lower basin. We need better accountability over transboundary natural resource governance in the Mekong.”

THE MEKONG UNDER THREAT

The Mekong River in Chiang Rai has already experienced severe ecological devastation in recent years due to dam construction on the river’s upper reaches in China. At least eleven dams have been completed on the Lancang or upper Mekong, with the Jinghong Dam–the closest one to the Thai border–only about 340 kilometers away. Three more dams are slated for construction in the lower reaches of the river in neighboring Laos, including the Pak Beng dam, proposed for development by Chinese and Thai companies across the Mekong in Oudomxay, just 90 kilometers from the Thai border. Another is the Luang Prabang dam, proposed by Vietnamese and Thai developers and currently trying to get a power purchase agreement with Thailand.

Therefore, the rapids blasting project is part of a much larger plan for the Mekong, one that would transform the river from a life-giving watershed to an industrial corridor where transnational corporations profit at a staggering cost to local livelihoods and biodiversity.

Featured photo: Niwat Roykaew of the Chiang Khong Conservation Group| Photo courtesy of Goldman Environmental Prize