Nestled beside Asia’s last free-flowing river, the Salween Peace Park in Myanmar’s Karen State (officially called Kayin State) is protecting the rights of Indigenous Karen people to self-determination, cultural survival and environmental conservation.

By Pianporn Deetes, Thailand and Burma/Myanmar Campaigns Director

Introduction

In Myanmar’s Karen State, the Indigenous Karen people have turned a war zone into a peace park, drawing on their culture and traditional knowledge to protect their ancestral lands.

The Salween Peace Park spans 5,485 km2 of biodiverse landscape in the state’s Mutraw district and is managed sustainably by local Karen communities. For the Karen, the park serves as protection against the Myanmar Army’s ongoing military presence in the state and is a bold declaration that they can own their land according to customary law, manage their natural resources and protect the future for their children

I’ve been working with the Karen people on campaigns to safeguard the Salween River since 2002—a river of vital importance to ethnic people in China, Myanmar, and Thailand—so I’ve seen the idea for the park unfold over many years, and now, like a beautiful flower, it has bloomed.

From war zone to a peace park

Among other trips to the Salween, one was to attend theinauguration of the Salween Peace Park in December 2018. About 1,000 people came to the launch, most of them members of Karen communities from Mutraw and other districts. When they declared the Salween Peace Park open, it was a moment for the communities to share with the world the importance of their ancestral lands, and of the Salween River and its tributaries, to their lives and livelihoods.

The communities’ inclusive approach to creating the park has been critical to its success. Everyone has been involved, men and women, elders, young people, students and farmers, and it’s this participation of all members of society that has made the park—and the broader movement for river protection—so full of life and hope.

A community-led approach

Community elders took the time to show me parts of the park, including some of the farms and fisheries near the village where I was staying. The park’s territory encompasses 27 community forests, four forest reserves, three wildlife sanctuaries and 132 customary land holdings. It’s such a positive model of a bottom-up, community-led approach to sustainable development, which according to the park’s charter, is about “ensuring that the natural environment, which forms the bedrock of Indigenous Karen people’s way of life, will continue to be healthy and plentiful.”

Women carry the park’s heart

When we returned to the village, the women prepared a delicious meal of fragrant rice bound in leaves. Women are the ones who carry the heart of the Salween Peace Park. When we’ve organized gatherings to express community concern over plans for large hydropower dams to be built on the Salween River, I’ve seen that women are in the front row. They want Myanmar, Thai and Chinese governments and companies to know that their lives will be devastated if the dams are built and the Salween Peace Park is inundated, displacing them from their villages. So women play a critical role, both in defending the existence of the park, and in protecting their families and communities.

Taking care of culture

During my time in the park, I’ve seen the way women are taking care of their families, taking care of their farms, and taking care of the culture of the Karen people.

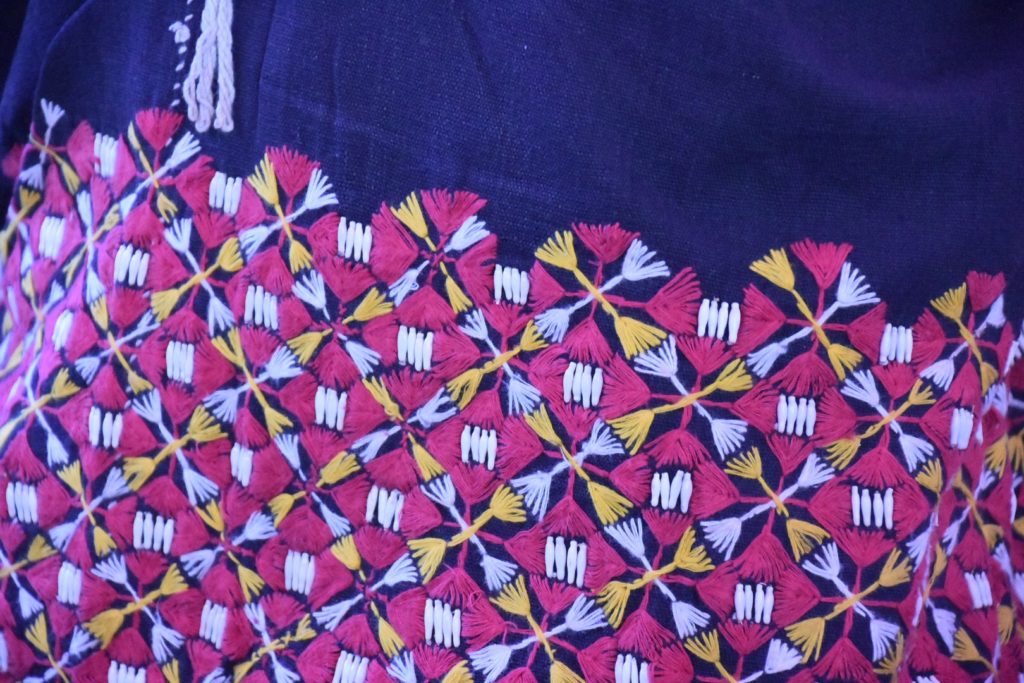

Women are primarily responsible for weaving the Karen’s traditional cotton clothing and hand-embroidering the distinctive decorative designs. Each pattern represents something from nature, in this instance the beautiful pink flowers that bloom on the maker’s farm. Other designs might feature images of butterflies and insects that help to pollinate their crops. All these patterns are so meaningful and are connected to the way the women grow rice and taro, and dozens of other fruits and vegetables on their farms.

Women understand ‘the small things’

Women play an important role in maintaining Karen cultural traditions and keeping them strong for future generations.

The two women pictured here showed me an exhibition of their work on display in the park, including intricately embroidered blouses and hand-woven baskets. Both have been actively involved in establishing the park, with the park’s democratic governance structure actively increasing women’s opportunity to take on leadership roles. They explained to me that while men tend to focus on the principles and concepts of the peace park, it’s the women who understand ‘the small things’, the day-to-day realities of caring for families, farms and culture, so their meaningful participation has ensured critical details have not been overlooked.

One of the last free-flowing rivers

The peace park’s eastern edge flanks the Salween River, pictured here, on the Thailand/Myanmar border. The Salween is one of the last and longest free-flowing rivers in the world, and inextricably linked to the Karen people’s lives, livelihoods, and cultural traditions.

Working for two decades with local communities, civil society, academics, journalists, and allies, we’ve had some huge wins in postponing destructive dam projects planned for the river. Now, looking ahead, we’d like to see permanent legal protection for the Salween.

I’m proud to be able to work with our Salween partners. For those working in ethnic areas of Myanmar, they have endured years of armed conflict, militarization, and human rights violations, yet they continue to stand up for communities’ rights and work to protect their culture and precious environment.