by Siziwe Mota, International Rivers Africa Program Director of International Rivers and introduction by Nalori Chakma, South Asia Senior Programme Coordinator, Transboundary Rivers of South Asia

Introduction

Globally, Indigenous rights to self-determination in relation to their rights to lands, territories and resources have been gaining support and attention at different levels. However, despite this a growing body of decisions of UN human rights bodies, regional and national courts and complaint mechanisms demonstrate that Indigenous Peoples continue to be the victims of human rights abuses associated with development and business activities, either by the State or Private actors.

Following the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, a growing number of investors, financial institutions and businesses in a range of sectors have developed, or are in the process of developing safeguard policies that require them to respect Indigenous Peoples’ rights, especially their right to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) as part of their “social license to operate.” Furthermore, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights on Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states the requirement for FPIC of Indigenous Peoples before: (a) their relocation from their lands or territories, including an agreement on just and fair compensation and, where possible, with the option of return (art. 10); (b) adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them (art. 19); (c) storage or disposal of hazardous materials on their lands or territories (art. 29.2); and approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources (art. 32). The UNDRIP has been adopted by 148 countries including Namibia and Angola. This was following the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Convention 169 which, (although Angola and Namibia have not ratified), seeks to ensure that governments consult indigenous peoples, through appropriate procedures and through their genuine representatives, whenever it is considering legislative or administrative measures which may affect them directly.

Community Protocols

Correspondingly, indigenous communities are increasingly developing their own community protocols and policies, to provide guidance to states and corporations on how to consult and seek their consent in accordance with their right to self-determination and their customary decision-making practices. Communities from the Murut Tahol Community in Alutok, Ulu Tomani, Tenom, Malaysia, the Juruna People in the Brazilian Amazon and the Embera Chami in Colombia are among those who have developed such protocols. These protocols illustrate closely the community’s identity, culture, ways of life and the interconnection of their places of being, between humans and nature. They illustrate the community’s strengths and needs to be recognized legally to voice out the decisions and participation of Indigenous Peoples in their plans, priorities and visions for the future.

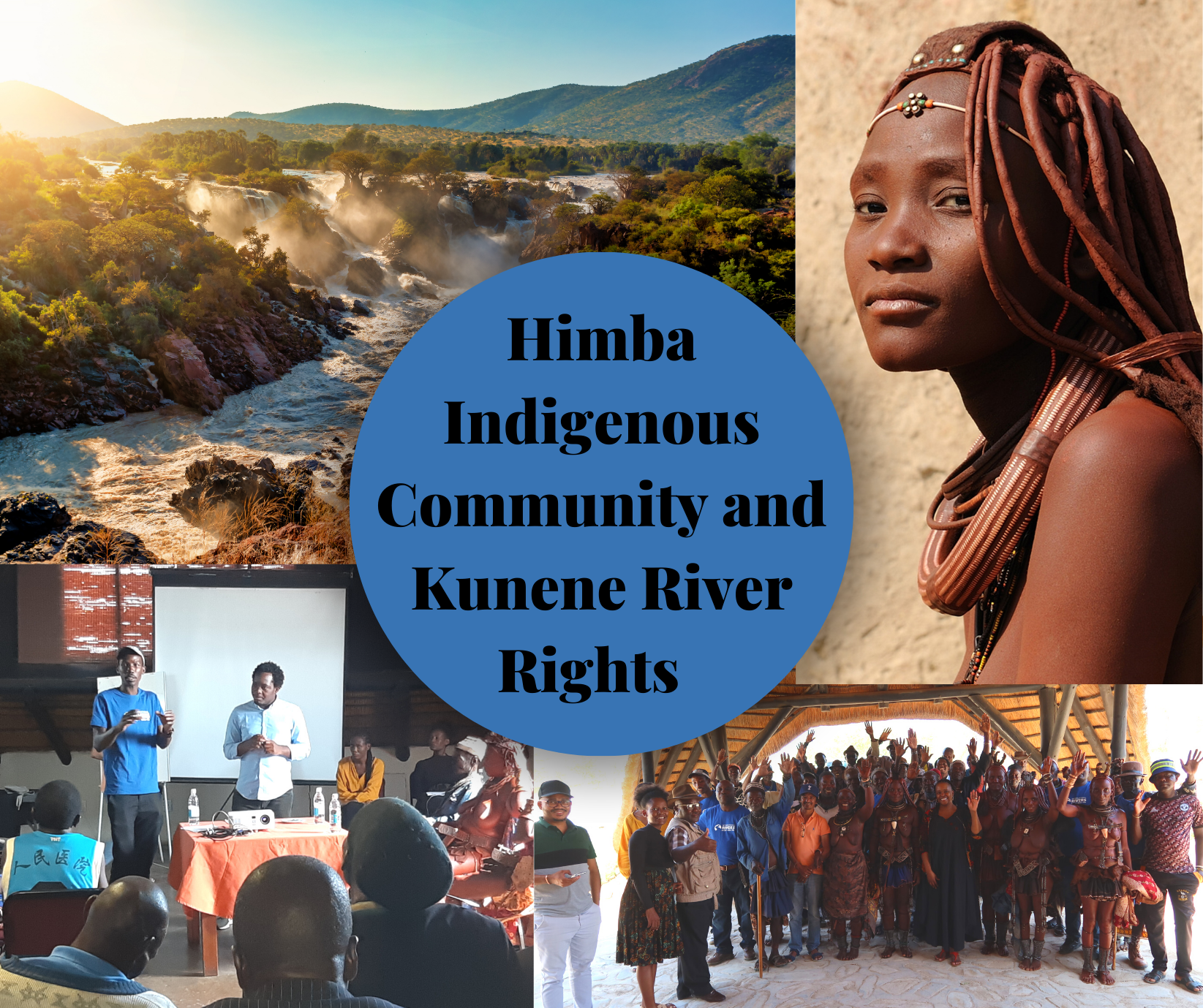

The Himba people

The Himba are closely related to the Herero who now mainly live in central and eastern Namibia. They are an ancient, semi-nomadic pastoralist people residing on the Angolan and Namibian sides of the Kunene River. The Kunene River valley is the ancestral home of the Himba people who have lived there for more than 500 years.

They have retained their way of life as successful cattle, sheep and goat farmers with large herds of up to 500 per family. Their economic independence is directly linked to the land and their livestock. Their semi-nomadic pastoral way of life, adopted because of the need to move between cattle posts in search of better grazing and water for their livestock, is perfectly adapted to the harsh climatic conditions found in the Koakaveld and as a result they are amongst the most successful cattle farmers in Namibia.

The role of community protocols in implementing Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in the protection of the Himba and other Indigenous Peoples’ rights in Namibia

The Indigenous Peoples of Namibia include the San, the Ovat jimba, Ovatue and Ovahimba, and potentially a number of other peoples, including the Damara (ǂNūkhoen) and Nama. Taken together, these Indigenous Peoples represent 8% of the total population of the country, which was 2,630,073 in 2020. The Namibian government prefers to use the term “marginalized communities” when referring to the San, Ovatue and Ovatjimba, support for whom falls under the Office of the President in the Division for Marginalized Communities (DMC). The Constitution of Namibia prohibits discrimination on the grounds of ethnic or tribal affiliation but does not specifically recognize the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Namibian government has also begun to recognize traditional authorities (TAs). However, TAs must be approved by the state and are often forced to support government policies, which undermines their autonomy.

The Himba and their FPIC rights:

The UNDRIP recognizes that Indigenous Peoples possess collective rights which are indispensable for their existence, well-being and integral development as peoples. To exercise these collective rights, FPIC exists and Indigenous Peoples are entitled to it. FPIC is a set of principles that defines the process and mechanisms that applies specifically to Indigenous Peoples in relation to their self-determination, rights to land, territories and resources, cultural identity and heritage. Indigenous Peoples can and should be able to decide for themselves on their own development. In this case, the Himba people must be able to proactively set their own priorities, guidelines and rules of their territories and resources. They should be able to exercise full sovereignty over their life as a community, their territory, the lands it encompasses and the other resources it holds. In this way, the Himba can fully exercise self-governance and enjoy the collective right of self- determination through their own decision-making processes by developing or documenting their community protocols.

Community protocols are practices, rules and responsibilities that are either orally passed on or written documentation by Indigenous Peoples of their Indigenous Knowledge to their land, territories, governance systems and natural resources. It encompasses indigenous knowledge of Indigenous Peoples, which is a complex body of wisdom, skills and practices developed over ages of their lifeways with distinct relationships within their communities and with their surrounding environment, which has been transmitted from one generation to the next in customary forms. They can be used as catalysts for constructive and proactive responses to threats and opportunities posed by land and resource development, conservation, research, and other legal and policy frameworks. It is documented, developed, used and enforced by the community.

| Community Protocols are referenced in the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization under Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The parties committed to support the development of community protocols by ILCs, and to take into account community protocols and other community rules and procedures where traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources is concerned. This is the first internationally binding acknowledgment of community protocols. |

First Consultation with the Himba towards developing their Community Protocol

At the end of March 2022, over a period of two days, International Rivers and Natural Justice held the first Community Protocol consultative workshop with representatives of the Himba from Namibia and Angola. The 40-plus participants represented traditional leadership, men, women and youth from the community. The objective of the meeting was to support the Himba to understand the purpose and benefits of developing a community protocol, to learn from indigenous communities who have developed these in Southern Africa and for them to start the process of developing and producing their own protocol.

On the first day, we set the stage by unpacking who the Himba are. What their history, values and traditions are and what makes them different from other communities. We also explored how the Himba relate to their land, sacred sites, spirituality, and ancestors, water, fruit, animals as well their beliefs with regards to the land and river. We also considered what are some of the challenges and threats that they face.

The Himba shared that culturally they are Hereros originally from Central Africa who settled in the Kaokaveld. In 1918, the Namas found them and waged war against them with guns which drove them into Angola. When they returned from being refugees in Angola they came back with the name Himba which means ‘beggars’.

Participants narrated that they have a strong belief in their culture, they believe in family and their bloodline and that holy fires, ceremonies related to burials and funerals, marriage rituals, communication with ancestors and the graves of their ancestors are all important and very significant to their spirituality.

They detailed that the Himba get buried by the river and on river islands where their ancestors were also buried and no matter the capacity of the river those graves are never covered. Grave sites hold such importance that they can never remove the body from the grave and move it somewhere else which was done after independence and is a huge injustice to them.

“The Kunene River is very significant for our culture for a number of reasons. It provides life to our livestock, for cultivation and because of the graves of our ancestors. We fight not only for the perennial rivers like the Kunene but also the seasonal rivers. That’s why we always say Don’t Block the Rivers!”– Chief of Otjurunga Traditional Authority

As an indigenous community, they face threats such as people trying to push their tradition to the edge and kill their culture with their laws. They regret that educated people pretend to help, but exploit their resources, and the people from the communities that get educated often come back confused and are there to create wealth for those who educated them. Although they agree with education, they want their children to be allowed to wear their traditional attires in schools.

“So, if you don’t want our children to wear their attire, don’t judge us if we keep them at home because that will be killing our culture”, member of the community lamented.

Another threat discussed was that there are natural resources that are discovered in a certain place that are supposed to be used for those communities where it is discovered, but that is not the case.

Additional threats are that some chiefs are recognized by the government and others are not. One of the Chiefs bemoaned that “Chiefs are chosen by the people but the government doesn’t want to recognize them, and will recognize somebody with 20 votes but not the one voted by thousands of people.” They believe that maybe this is so that they can take their natural resources.

On the second day, we unpacked indigenous people’s rights, looking at a national, regional and international law. Natural Justice looked at Namibia’s laws as relates to Constitutional protections for Indigenous Peoples, legal protections for Indigenous Peoples, and Namibia’s National Policy on Indigenous Peoples.

International law on FPIC was reviewed considering UN treaties and other international instruments such as UNDRIP; ILO 169 Article 6 (1), Article 7 (1), Article 15; World Commission on Dams (2000) “Public acceptance of key decisions is essential for equitable and sustainable water and energy resources development. Acceptance emerges from recognizing rights, addressing risks, and safeguarding the entitlements of affected people, particularly indigenous and tribal peoples, women and other vulnerable groups…”; UN Economic and Social Council’s Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights “Transnational corporations and other business enterprises shall…respect the principle of FPIC of the IPs and Communities…to be affected”.

International Rivers unpacked the Importance of rivers, why and how the Kunene River can potentially be protected and preserved through a Rights of Rivers approach.

On the second day, Community Protocols were also introduced. What they are, what is the process of developing them and how have they been used in other contexts. This was expanded on by Natural Justice and examples of how other indigenous communities had developed and used community protocols were discussed. The Himba collectively agreed to work together with seven (7) representatives of the different villages to develop a Himba Community Protocol which would seek to ensure that decision-makers recognise, respect and uphold the collective rights of the Himba through a meaningful consultation, that their autonomy and self-determination are recognized and that the land, and natural resources of the Himba are recognised and protected in accordance with their self-governing system.

Read Part Two: https://www.internationalrivers.org/news/mapping-community-protocols-with-himba-leaders/