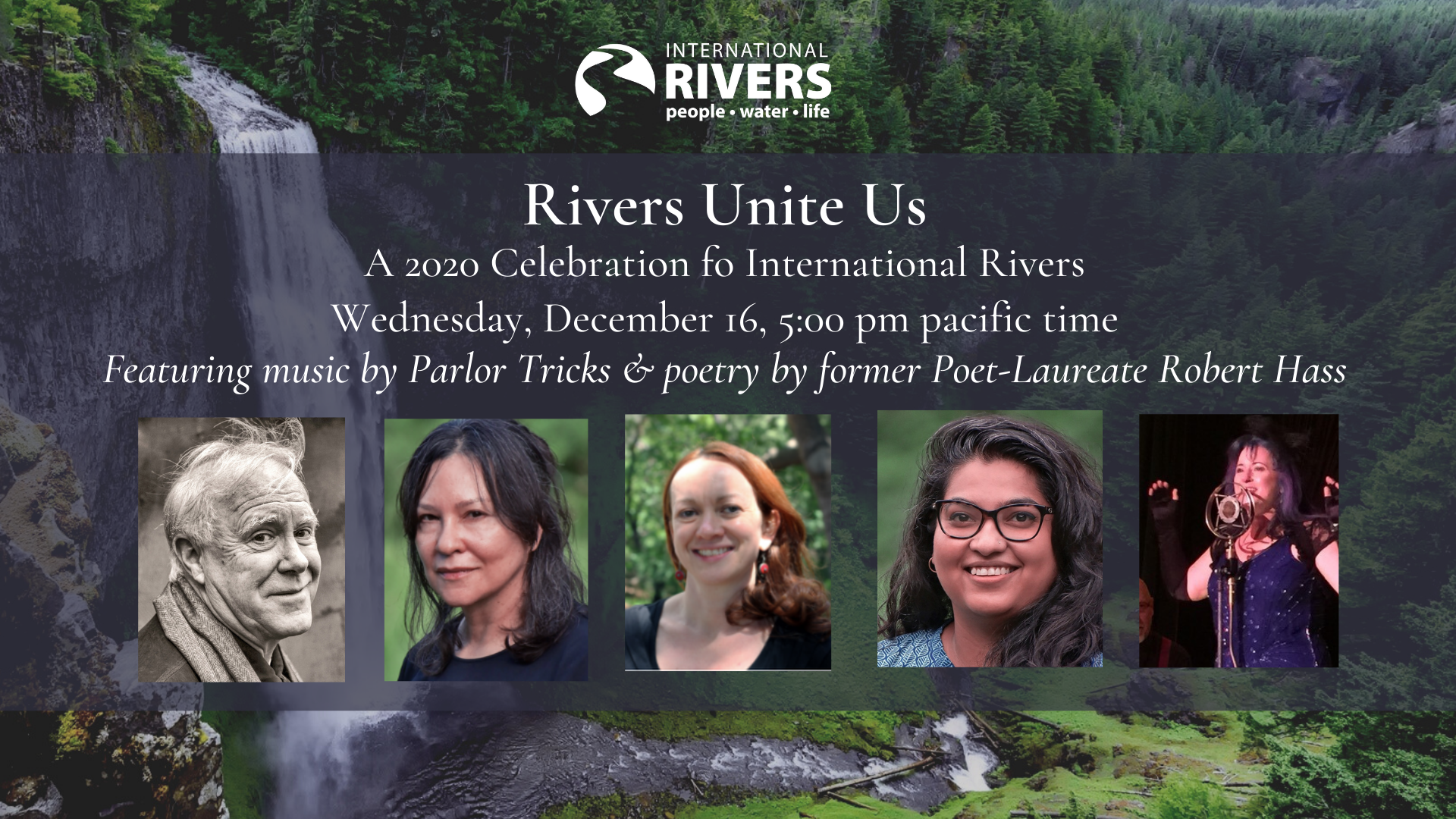

Poet Laureate Robert Hass is joining us live on December 16 at 5pm pacific for our 2020 end of the year event “Rivers Unite Us” for a live reading.

A RIVER from “The State of the Planet”

The people who live in Tena, on the Napo River,

Say that the black, viscous stuff that pools in the selva

Is the blood of a rainbow boa curled in the earth’s core.

The great forests in that forest house ten thousands of kinds

Of beetle, reptiles no human eye has ever seen changing

Color on the hot, green, hardly changing leaves

Whenever a faint breeze stirs them. In the understory

Bromeliads and orchids whose flecked petals and womb-

Or mouthlike flowers are the shapes of desire

In human dreams. And butterflies, larger than a child’s palm

Held up to catch a ball or ward off fear. Along the river

Wide-leaved banyans where flocks of raucous parrots,

Fruit-eaters and seed-eaters, rise in startled flares

Of red and yellow and bright green. It will seem like poetry

Forgetting its promise to be sober to say that the rosy shinings

In the thick brown current are small dolphins rising

To the surface where gouts of oil are oozing from the banks.

Oil companies want the oil, of course, and energy companies

Want the current which the river dolphins ride as if

The power of life the river gathers to itself were purely play,

were the living force in things and purely play.

Note: This poem was written in 1998 for the 50th anniversary of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (a center for climate research) at Columbia University. Below is the latest news from the Napo River where fifteen hydroelectric dams were in planning stages or under construction. Ecuador is in a deep economic and health crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic that has spread seriously in the city of Guayaquil, in the province of Guayas. Amid that crisis, at 7:15 p.m. on Tuesday, April 7, part of the riverbed of the Coca River, located on the San Rafael sector and on the border between the provinces of Napo and Sucumbíos, sank. The resulting sinkhole caused the collapse of upstream infrastructure belonging to the Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System (known by its Spanish acronym SOTE) and the heavy crude pipeline (operated by private company OCP), which then caused an oil spill on the Coca. One expert interviewed by Mongabay said she believes the waterfall’s collapse and subsequent heavy erosion events are linked to the Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant, which was built and financed by Chinese companies.

Ezra Pound’s Propositions

Beauty is sexuality, and sexuality

is the fertility of the earth and the fertility

Of the earth is economics. Though he is no recommendation

For poets on the subject of finance,

I thought of him in the thick heat

Of the Bangkok night. Not more than fourteen, she saunters up to you

Outside the Shangri-la Hotel

And says, in plausible English,

“How about a party, big guy?”

Here is more or less how it works:

The World Bank arranges the credit and the dam

Floods three hundred villages, and the villagers find their way

To the city where their daughters melt into the teeming streets,

And the dam’s great turbine, beautifully tooled

In Lund or Dresden or Detroit, financed

by Lazard Freres in Paris or the Morgan Bank in New York,

enabled by judicious gifts from Bechtel of San Francisco

or Halliburton in Houston to the local political elite,

Spun by the force of rushing water,

Have become hives of shimmering silver

And, down river, they throw that bluish throb of light

Across her cheekbones and her lovely skin.

RIVERS by Czeslaw Milosz, translated by the author and Robert Hass

Under various names, I have praised only you, rivers.

You are milk and honey and love and death and dance.

From a spring in hidden grottoes, seeping from mossy rocks

Where a goddess pours live water from a pitcher,

At clear streams in the meadow, where rills murmur underground,

Your race and my race begin, and amazement, and quick passage.

Naked, I exposed my face to the sun, steering with hardly a dip of the paddle—

Oak woods, fields, a pine forest skimming by.

Around every bend the promise of the earth,

Village smoke, sleepy herds, flights of martins over sandy bluffs.

I entered your waters slowly, step by step,

And the current in that silence took me by the knees

Until I surrendered and it carried me and I swam

Through the huge reflected sky of a triumphant noon.

I was on your banks at the onset of Midsummer Night

When the full moon rolls out and lips touch in the ritual of kissing—

I hear in myself, now as then, the lapping of water by the boathouse

And the whisper that calls me in for an embrace and consolation.

We go down with the bells ringing in all the sunken cities.

Forgotten, we are greeted by embassies of the dead

While your endless flowing carries us on and on;

And neither is nor was. The moment only, eternal.

Robert Hass on Rivers and Stories

Though the names are still magic – Amazon, Congo, Mississippi, Niger, Platte, Volga, Tiber, Seine, Ganges, Mekong, Rhine, Colorado, Marne, Orinoco, Rio Grande – the rivers themselves have almost disappeared from consciousness in the modern world. Insofar as they exist in our imaginations, that existence is nostalgic. We have turned our memory of the Mississippi into a Mark Twain theme park at Disneyland. Our children don’t know where their electricity comes from, they don’t know where the water they drink comes from, and in many places on the earth the turgid backwaters of dammed rivers are inflicting on local children an epidemic of the old riverside diseases: dystentary, schistosomiasis, “river blindness.” Rivers and the river gods that defined our civilizations have become the sublimated symbols of everything we have done to the planet in the last two hundred years. And the rivers themselves have come to function as trace memories of what we have repressed in the name of our technical mastery. They are the ecological unconscious.

So, of course, they show up in poetry. “I do not know much about gods,” T. S. Eliot wrote, who grew up along the Mississippi in St. Louis, “but I think that the river is a strong brown god.” “Under various names,” wrote Czeslaw Milosz, who grew up in Lithuania along the Neman, “I have praised only you, rivers. You are milk and honey and love and death and dance.” I take this to be the first stirrings, even as our civilization did its damming and polluting, of the recognition of what we have lost and need to recover.

When human populations were small enough, the cleansing flow of rivers and their fierce floods could create the illusion that our acts did not have consequences, that they vanished downstream. Now that is no longer true, and we are being compelled to reconsider the work of our hands. And, of course, we are too dependent on our own geographical origins to have lost our connection with them entirely.

It may have been in Roman times that the Danube acquired its common name, since the Romans were great makers of maps, though it had probably been, long before any legions marched along its banks, a local god in many different cultures, with many different names. I knew of one poem, by the Belgrade poet Vasko Popa, that addresses Father Danube in a sort of Serbian modernist prayer:

O great Lord Danube

the blood of the white town

Is flowing in your veins

If you love it get up a moment

From your bed of love—

Ride on the largest carp

Pierce the leaden clouds

And come visit your heavenly birthplace

Bring gifts to the white town

The fruits and birds and flowers of paradise

The bell towers will bow down to you

And the streets prostrate themselves

O great Lord Danube

Rivers flow like stories and like stories they have a beginning, a middle, and an end. In between, they flow. Or would flow, if we let them. It’s interesting to consider the fact that, in popular culture, in commercial television, what’s happened to rivers has happened to stories. A dam is a commercial interruption in a river. A commercial is a dam impeding the flow of a story: it passes the human imagination through the turbine of a sales pitch to generate consumer lust.