Originally published in Bangkok Tribune News

By Phairin Sohsai, the Thai-Mekong Campaign Coordinator for International Rivers and Sayan Chuenudomsavad, a documentary photographer residing in Bangkok, Thailand. Diverse and vibrant, his images capture everyday people living alongside the challenges of development, climate change and social changes in the Mekong region.

The Northeastern region has been dotted with dams following the decades of state ambition to make optimum use of water in the region and from the Mekong River. They, however, have also been marred with strong opposition by local people who say the environment and their livelihoods have been extensively affected

For the past few decades, the water from the Mekong River and its tributaries has been offered as the main ‘solution’ to address drought and poverty and bring prosperity to the people of Isaan, the Northeast of Thailand.

Water shortages and limited productivity are often viewed as a problem of the country’s Northeast, driving large-scale water resource development interventions since at least the 1960s when modernisation of the agricultural sector became a key ideological underpinning of state development policy in Thailand.

During the Second Indochina War, building dams and large water infrastructure in Thailand’s Northeast region was part of Thai-US counter-insurgency or development programs in their fight against communism. As Cold War tension eased, the “Green Isaan” project was promoted to irrigate the Northeast and promote agro-industrial development.

A long line of large-scale water development projects has ensued and many Isaan people have come to believe the political slogan, “bring water to Isaan and poverty will be made history”. As a result, Isaan is littered with dams and reservoirs like the Ubonrattana Dam, Lam Pao Dam, Sirindhorn Dam, and Pak Mun Dam. Despite billions of baht being spent, these projects have done little to improve the lives of Isaan people or reduce inequalities.

One of the most controversial water development initiatives, the Kong-Chi-Mun Project, aimed to pump water from the Mekong and key tributaries to irrigate Isaan. More than 18 billion baht was allocated to develop at least 14 dams and irrigation systems in the first phase on the Mun and Chi River systems. The aim was to increase the irrigated area to more than four million rai (640,000 hectares).

The impacts

The promised benefits never materialised. On the contrary, the project caused widespread salinisation of irrigated land and destroyed one of the most ecologically abundant wetlands in Isaan. The lowland floodplain forest used to be the breeding ground of more than 200 species of fish and other aquatic animals and was home to numerous native plants which people relied on for their livelihood. The reservoirs also inundated farmland and grazing land and hundreds of salt farms.

People mobilised in opposition to the state project as part of the “Assembly of the Poor” in the 1990s. These days they continue to demand compensation for the loss of land and livelihoods and the restoration of the ecosystem. As a result of these social conflicts, phase two of the Kong-Chi-Mun Project was shelved.

Despite the failure of the Kong-Chi-Mun and its predecessors, large-scale water development projects to alleviate “drought” and “poverty” in Isaan continue to be a flagship policy of successive governments and political parties. It seems that nothing much has changed except the name of each proposed project, and the political stripes of its proponents.

The Office of National Water Resources (ONWR) and the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) are still trying to resurrect the Kong-Loei-Chi-Mun Water Management by Gravity Project. With a cost estimate of over 2 trillion baht, the project seeks to divert water from the Mekong River to Ubonrattana Dam to supplement the Khong-Chi-Mun irrigation project.

The project has several components, including expanding the mouth of the Nam Loei River, a tributary of the Mekong River, and diverting water through mountains via tunnels that traverse through protected areas and villagers’ farmlands. In the view of the local people, this is more or less an attempt to “build a new river in Isaan”.

This project is also linked with the proposed development of the Pak Chom Dam on the Mekong River along the Thailand-Laos border. The idea is to elevate water in the Mekong so as to enable it to flow into the Nam Loei River and the water diversion system in Isaan.

The Kong-Loei-Chi-Mun Water diversion project’s environmental impact assessment is still at its initial phase and is under the review of the Expert Review Committee. However, there are concerns over the project’s high cost and its ability to deliver irrigation benefits, as well as the negative environmental and social impacts.

Additionally, the RID has indicated that it wants to revisit old plans to build a few dams on the Songkhram River, causing much concern among local people.

The Songkhram River features a unique wetland ecosystem, which has been compared to Cambodia’s Tonlé Sap. The area is teeming with biodiversity and is a critical nursing ground for fish from the Mekong River during the rainy season.

Last year, Songkhram was designated a Ramsar site under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, making it the 15th site in Thailand. Songkhram’s biodiversity and richness stem from local community efforts to preserve and sustainably manage the wetlands, which are important for their culture and livelihood. Its designation as a wetland of international importance should provide additional protection from large-scale projects in the future.

In conclusion, large-scale water infrastructure has failed to address poverty in Isaan. Many environmental and social impacts from existing projects remain unaddressed. Yet, it seems the Thai government has not learnt lessons from the failure of previous large-scale projects.

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

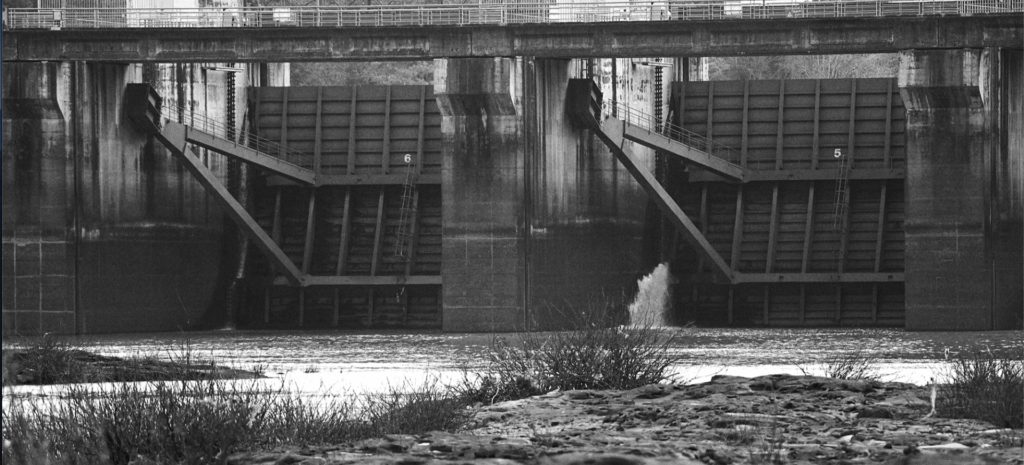

Posters and signs expressing strong opposition are extensively erected in the villages. The villagers refuse to call it “a sluice gate” but a dam, the terms which state official try to avoid to use.

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

The Saga of Mekong Tributary Dams is part of the exclusive photo essay series, the Mekong’s Womb, to present to the public the values of the river basins and tributaries of the country and the Mekong region, their rich biodiversity, unique landscape and geography, livelihood and culture, which could soon vanish without a trace because of rapid development in the region.

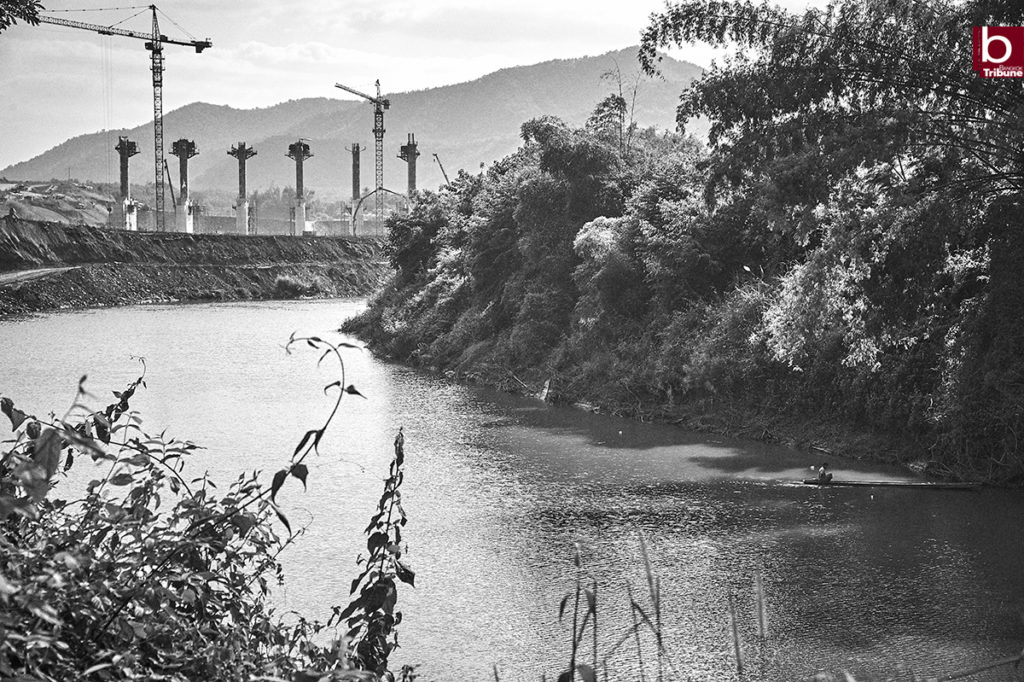

Featured photo: Sri Song Rak sluice gate on the Nam Loei River in Loei’s Chiang Khan district is under construction and is expected to be completed by this year. It is among the first infrastructures of the rebranded Kong-Loei-Chi-Mun mega-project attempting to make optimum use of water from the Mekong River. Photo: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad