Two decades of indigenous peoples working to keep the Salween River free-flowing

By Pai Deetes, Thailand and Myanmar Campaigns Director of International Rivers

Originally published in the Bangkok Post

On a sandy beach by the Salween River on the Thai-Myanmar border in March 2006, boats carrying Karen villagers and other ethnic groups such as Karenni, Yintalai and Shan from various areas in the Salween Basin are arriving to join an important yet simple ceremony.

Once the 600 participants were ready, a Christian pastor prayed to God. Then a monk lit candles and did a blessing.

Old Karen spiritual leaders performed a ritual to pay respect to the spirits that protect the river and forest. On this day, indigenous peoples of the Salween were grouped according to their religions and beliefs, gathered together along the river.

All of this was held together to show the villagers’ collective stance to protect the Salween River from dam construction that would be destructive to the river’s ecology, biodiversity, and to their livelihoods.

At that time, the Chinese, Myanmar and Thai governments had plans to build up to 20 hydroelectric dams along the river, in China and Myanmar as well as on the Thai-Myanmar border.

That was the first time that the peoples of the Salween organised their local March 14 International Day of Action for Rivers event. This event is part of a global movement that originated from a meeting of people affected by dams around the world, held in Curitiba, Brazil, in 1997.

Over the past two decades, the Salween River has been a target for the hydropower industry. However, because of indigenous peoples’ long-standing efforts, the Salween is one of the last transboundary rivers in the world that still flows freely.

Originating from the melting snow in the Himalayan plateau, the Upper Salween or Nu Jiang, flows alongside the Mekong River and the Yangtze River into Yunnan Province of China. The area is designated as a World Natural Heritage Site by Unesco.

The Salween River enters Myanmar through the heart of Shan State, then flows to Karenni State before forming a border between Thailand and Myanmar and between Karen State and Mae Hong Son province.

It then flows back into Myanmar before entering the Andaman Sea in Mawlamyine, Mon State, with a total length of approximately 2,800 kilometres.

In 2003, China had plans for a cascade of 13 dams on the Upper Salween River. But the plan has been halted several times due to opposition from civil society organisations and local riverine communities, and due to awareness raised by extensive media coverage.

In Myanmar, there are at least seven dam projects proposed, all driven by state-owned enterprises and companies from Thailand and China.

On the Day of Action for Rivers event in 2006, peoples of the Salween gathered to protect the river from two dam projects on the Thai-Myanmar border; the Wei Gyi and Da-gwin dam projects proposed by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Egat). Eventually, because of strong grassroots movements along with concerns from conservation groups about the destructive environmental impacts, the projects were shelved.

At another Day of Action for Rivers, in 2007, an event was held on a beach in Karen state opposite Ban Sop Moei, Mae Hong Son province. There were hundreds of Karen people from both sides of the river. At that time, the Hat Gyi dam project was in planning for construction on the Salween River in Karen State, just 47 kilometres from the Thai border. It was also an Egat project.

In Shan State, almost every year since 2006, the Shan people hold Day of Action for Rivers events in different areas, as there has been a plan for three dam projects including Mong Ton dam (also known as Tasang), Kun Long dam and Nong Pha dam. The gatherings clearly show the efforts of the Shan people who want to save the Salween River, which is in a region that has been under civil war for decades.

If built, Mong Ton dam will submerge the “Thousand Islands” on a tributary of the Salween, the Pang River, which possesses unique ecological importance and beauty where the clear blue river flows around hundreds of islands.

It is a part of the area where more than 300,000 Shan people in 150 villages have been forced to relocate by Burmese military dictatorships since the late 1990s. This has involved human rights violations by the Burmese army including the uprooting of tens of thousands of Shan peoples who are still displaced today.

In Karenni State, various ethnic villages have continually organised Day of Action events to oppose the plan for the Ywatith dam on the Salween. Karenni State also faces heavy attacks by the Myanmar military junta which has caused the displacement of over 170,000 people due to clashes and airstrikes since May 2021.

This year, there will be events on the Salween River at several areas calling for its permanent protection.

In Karen state, indigenous peoples in Salween Peace Park will take a stand calling for the Myanmar junta to stop the attacks and withdraw from their ancestral lands, as well as stop the plan for dams on the Salween River.

In Thailand, there will be activities at Sob Ngao, the confluence of the Ngao River, a tributary of the Yuam River in Mae Hong Son province.

The People’s Network of the Yuam, Ngao, Moei, and Salween Basin have monitored and opposed the Yuam water diversion for years. This trans-basin water diversion project has been proposed by the Royal Irrigation Department.

It is a 110-billion-baht investment which consists of a dam, large pumping station, high-voltage transmission line, and 62km underground tunnels that will destroy a lush forest ecosystem that spans the three provinces of Tak, Mae Hong Son and Chiang Mai.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report has been criticised as being deeply flawed because the process did not properly obtain free, prior and informed consent and for a lack of public participation, especially from affected indigenous communities.

The EIA and water diversion project are being investigated by the Thai National Human Rights Commission and the Parliament Committee on Land, Natural Resources and Environment.

In addition, politicians who push the project are giving interviews to the media that suggest the diversion of the Yuam’s water will be just the beginning.

The proponents frequently say that a Chinese enterprise has offered to build the tunnel for “free”, in exchange for permissions for a “phase two” which would see Chinese-led dam construction on the Salween River in Myanmar.

For two decades, we have seen the seeds of grassroots efforts to protect the environment, biodiversity and human rights of indigenous people.

As people in Myanmar are facing life and death situations, especially after the coup, I still feel the resistance of the Salween peoples coming together for peace and the future of the Salween River to flow freely, as a source of life, culture and as a legacy for many generations to come.

Pianporn (Pai) Deetes is Regional Campaigns Director for Southeast Asia Program at International Rivers, a global NGO working to defend the rights of rivers and communities.

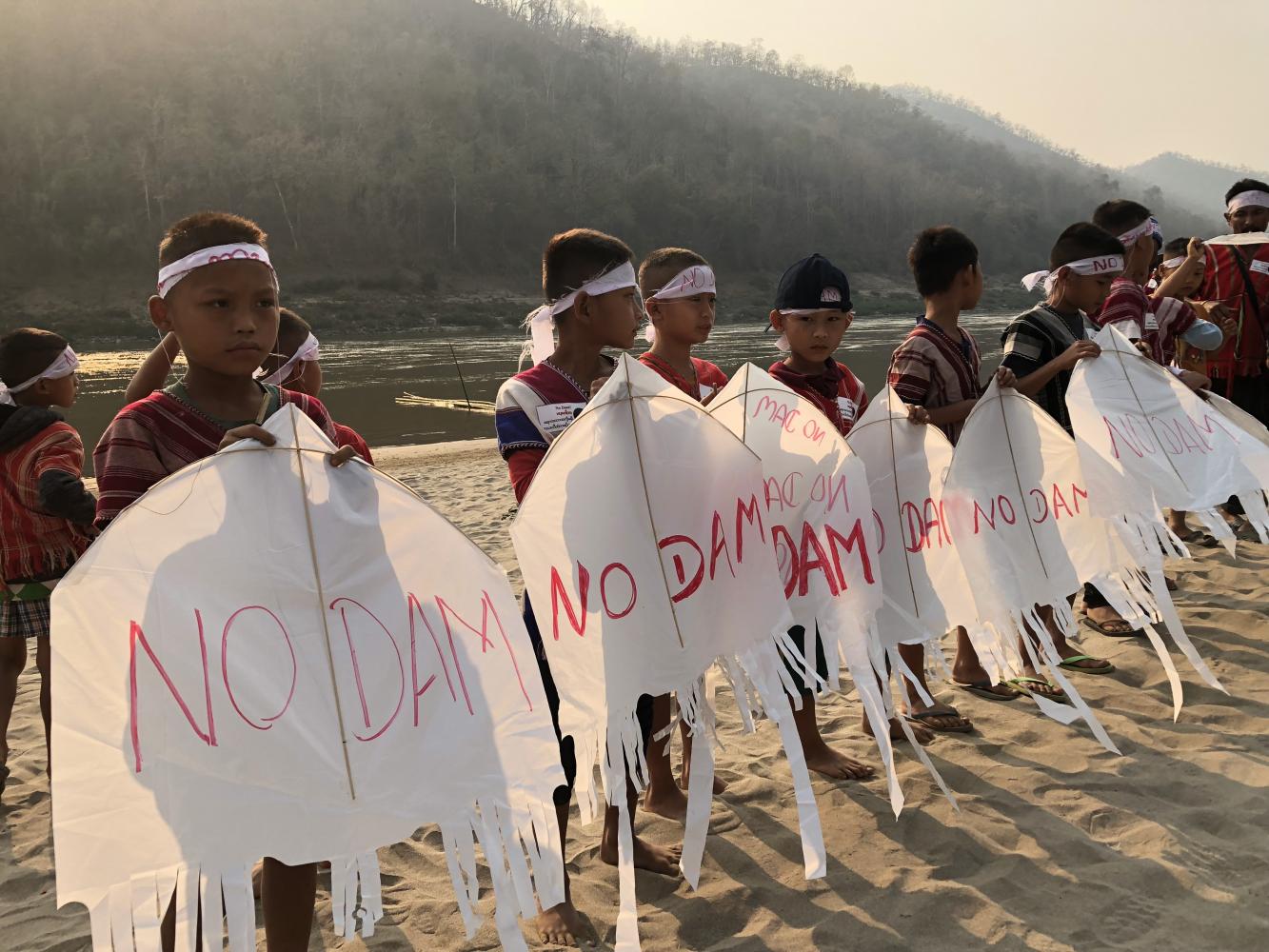

Featured photo: Karenni villagers along the Thai-Myanmar border join a campaign protesting against plans for hydroelectric dams on the river. Pianporn Deetes/International Rivers