By Petro Kotze

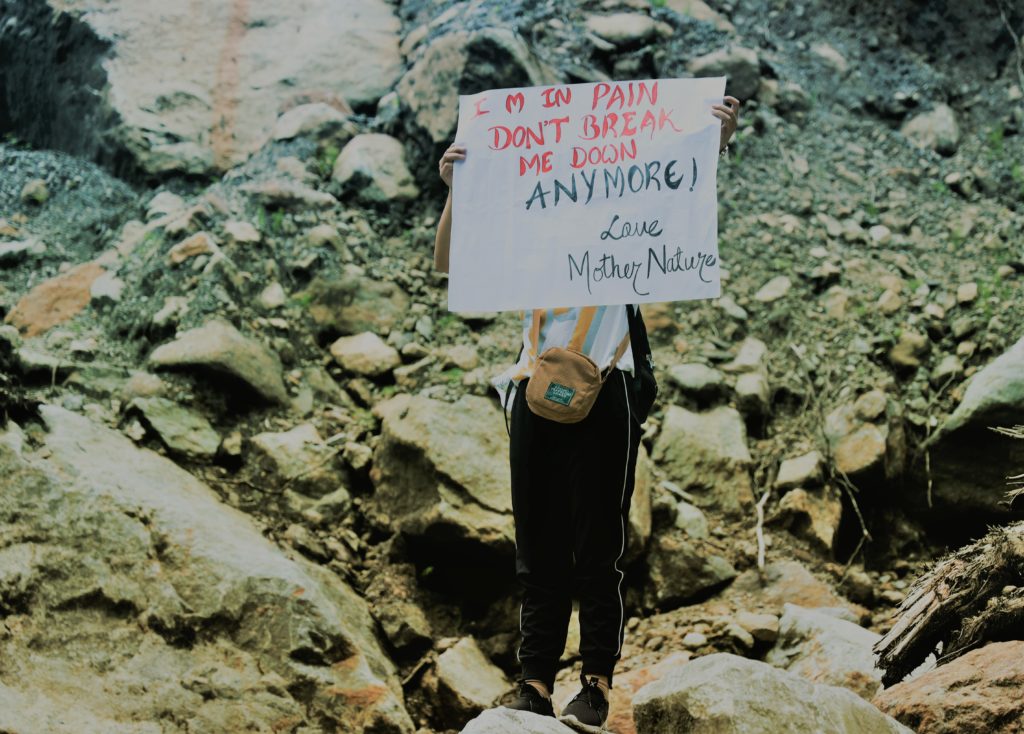

She fights for the survival of the only place she belongs

Some people already consider the Lepchas to be a vanishing tribe, says Marmit Lepcha, a Lepcha from Dzongu, in India’s North Sikkim region but, “this is where I belong.” I only understood this once I was away from my home, the Gnon Sangdon Village next to the Teesta River for a long time, she says. Marmit once spent six years in Chandigarh for her studies but now that she has returned, she is part of those that have taken up the fight to protect the Lepcha’s ancestral lands from development they consider a major threat to their environment, community, and culture.

Rivers are an integral part of the Sikkimese character. Their folklore and traditional ways of life revolve around the mighty Teesta. The river not only sustains their livelihoods but is the very backbone of their cultural heritage. However, the once free-flowing river has been broken by multiple hydropower projects constructed over the past 30 years.

Breaking the Teesta

The Sikkim provincial government has awarded contracts to private operators for 26 large hydropower projects on the Teesta River, seven of which would affect the Dzongu province. Already, only about 8 kilometers of the river remains free-flowing in the whole of Sikkim. This area is now earmarked for the 520 MW Teesta Stage IV hydropower dam project, between the Teesta III (under construction) and Teesta V (completed) dams. The construction and intake tunnel for Teesta IV’s dam will destroy a sacred lake, believed to be the heart of where a Lepcha clan originated.

A second dam, the 300 MW Panan Dam is planned for the heart of Dzongu on the Rangyong River, a tributary of the Teesta. The proposed location is a stone’s throw from the Kanchendzonga National Park and Biosphere Reserve. For more than three decades, the Lepchas have vehemently opposed the controversial developments and now, for Teesta Stage IV and the Panan Dam, Marmit has come home to help support their work.

A new generation takes up the baton

Through the years that she was away, Marmit followed the activities of the Affected Citizens of the Teesta (ACT), a local NGO that is leading the fight against the hydropower projects. Initially, she didn’t know much about their work, but realized that “whatever they were doing, it was for the good of not just the Lepcha people but for all the mountains, rivers, the flora and the fauna that we worship and enjoy.” She also realized that the elders who were fighting to save the last bits and pieces of the River Teesta needed help.

She moved back to Gnon Sangdon in 2018 and joined the ACT the following year. At first, she attended meetings and advocacy activities and now contributes to the organization’s social media campaigns. “My friends and I work together to spread awareness on social media, and to reach out and look for people who could add their voices to our team, she says. Over the years we have built a strong group in every corner of Dzongu and from outside the region as well”, she says. More than a team, Marmit says they have built a family of big groups. “Our thoughts and voices have reached many, and now we hope that the government too would lend us their ears.”

They are far still from their goal of getting plans for the Teesta IV and the Panan Project scrapped, Marmit says, but their work and the news of their struggles are at least being recognized by people. “The ACT has become a recognized and respected institute to environmentalists, anthropologists, and those involved in agriculture, horticulture, and cultural preservation, who count on us to help them access resources and information”, she says. In the process, their work has opened a door to ecotourism development too.

However, the immensity of what stands to be lost remains a very real threat.

Ancient culture in danger of disappearing

If the developments continue further, the very existence of the Lepcha community, the indigenous, original inhabitants of Sikkim, would stop. The Dzongu land is already severely degraded and soon, the protected land of Lepchas will disappear off the map of Sikkim, she says. Already, many people have lost their ancestral homes, their unique identity, and their self-respect as part of belonging to a community, she says.

For Marmit, the saddest part is to see her community split into opposing groups, for and against the development of the hydropower project. “The rich are getting richer and the poor are not only getting poorer but losing their only homes to this so-called development in the name of destruction.”

Marmit says she has learned that, in the end, to protect the environment and your identity, education doesn’t count. “I have seen people educated with degrees and in official positions that cannot speak but keep their ears and eyes shut to let injustice happen, she says. “In comparison, most of the women of Dzongu are illiterate, but they know enough to understand that selling your land and rivers and your identity is no way to make a living.” Marmit too has realized that her identity is closely linked to the Teesta. “The river has given her a sense of belonging,” she says.

Coming home

The time she spent away from Sikkim taught her the importance of where she was from, Marmit says.

“For me, every river is important, but the River Teesta especially so. It is the driving force of our existence.” Now that she knows what it is like to live without it, she says she cannot afford to miss the luxury of green forests again.

“A threat to the River Teesta is a threat to me, to my tribe, to my community, to my forest, and to all the living organisms that exist in and around River Teesta.” In the process of learning where she belongs, Marmit has also learned that her existence is as important to the future of her home, as it is to hers. To help protect the Teesta, her voice matters too. “Every voice matters,” she says, “and if you cannot speak and fight for yourself, no one will.”

International Rivers’ South Asia program is part of the regional Transboundary Rivers of South Asia program. Supported by the Government of Sweden, TROSA is a collaboration with Oxfam, IUCN, ICIMOD and many local organizations that works on some of the more complex rivers in South and Southeast Asia: the Ganga, Brahmaputra and Meghna river systems, including their tributaries such as the Teesta, and Asia’s last last free flowing river, the Salween. The program aims to contribute to poverty reduction and marginalization among vulnerable river basin communities through increased access to and control over riverine water resources on which their livelihoods depend.